AC|DC 2.1

September 2, 2025

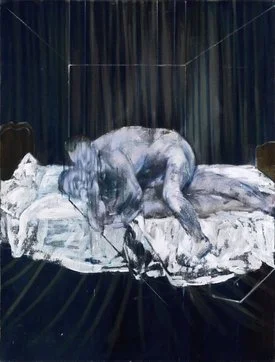

Two Figures

by Vera Podell

We didn’t fight the night before Richard left.

That was a routine and unbearably unmemorable morning. Richard had an early flight to Toronto where he was supposed to perform. It was my long-anticipated weekend alone. I don’t remember – but I probably was half asleep, finally, after a bout of insomnia, when he kissed me and said goodbye and I might have mumbled something like ‘See you soon’ and the next time I saw him, he was buried under the rubble of something that appeared to be a car just a few hours earlier. The cage was upside down, policemen and firefighters were rambling around. I could not see his face from where I stood. I didn’t cry. There is no way to prepare yourself for this, I think.

Strange – my memory is created out of patches – one over the other.

We met – that is the beginning. That night he was handsome in his own, most charming way (that’s how I remember it now, at least). We met after the opening night of an exhibition by we were both not really enthusiastic to attend. He was bored, I think, so he kept gazing at me the way I didn’t understand – was it predatory or innocent? We both were much younger then – his shoulder-length hair didn’t have a trace of grey yet. The morning he left his hair was tied into a messy bun that was disheveled under the wreckage of the car. The coroner likely had to pull glass shards out of it.

I am not sure where lies the void separating us and if it’s purely corporal. Now my chest starts to hurt the moments I least expect it to – when I am in a drugstore, or in the studio, or in a pub drowning myself in a tequila bottle. Richard always hated the alcohol I chose, was more of a whisky man. If he saw me now, as I am lying head down on the bar table trying not to weep and not to throw up, at least not simultaneously, he would click his tongue and say haughtily ‘You can do better than this’. But he is no longer here to judge. Trying to find any light in this loss, I stumble upon this thought more often than I’d like to.

I noticed barely visible blood spots on Richard’s white shirt when he was getting up on to the stage with the baton in his hand. I struggle to remember now whose blood that was. Maybe that was the day of one of our unusually raging fights. Or maybe his nose was bleeding and I didn’t bring him the towel while he needed it.

At the funeral his mum spoke to me. I recognized her from the pictures I saw scrolling through his phone. ‘Were you two close?’ she asked. ‘Yes, quite close actually’. I didn’t want to tell her anything but at the same time I urged to see her face as she realized what her son really was. ‘I am sorry for your loss’ she murmured. ‘So am I’. Richard really never bothered to tell her about me, during all those years. I was – I am – vane. He told me that. But he was no better in the slightest – completely arrogant, a little destructive from one side, a little destructed from the other. I was – I still am – hurt. But I do not give a shit about his mother, being sorry for my loss and my loss only.

His mom is not who I think about when I fuck. Now I don’t think about Richard either – and that’s a good thing. Sex stopped bringing pleasure a long time ago but it makes the mind foggy –achy and compelling. It’s never the sweaty bodies, heavy breathing and the erratic thrusts that make the experience worth the time spent, it is the silence of thoughts afterwards. The quieter the better, and the more deranged and shameful it gets behind closed doors, the longer the pause of the voices inside my brain is. Even when we were together, I needed that silence – and not like Richard wasn’t aware. We both preferred not to bring it up unless we wanted bad to really hurt each other. If he asked me now, I’d say that it’s the same thing he had with cigarettes – an ugly habit, but so what?

Smoking does kill – but one high on crack man behind the wheel of a red Chevrolet does the job much faster, huh?

Richard exclusively smoked strong cigarettes. Even when his nose bled, he wouldn’t stop. It happened regularly after his bouts of insomnia. He would hold the cigarette between his index and middle fingers and the blood would be running down his lips. I cussed at him for letting himself bleed that way, but I guess he in a way enjoyed it. During the performances, his nose bled only a couple of times, and the pictures from those days are the first thing you will stumble upon if googling his name. These pictures were even used to illustrate the news about his death – ‘A tragic accident took the life of a world-famous conductor’ followed by his real name. I was mad the at all those media outlets, even though I was the one monitoring all the news about him being gone. I still read every article where his name is mentioned. I put his name in Twitter search and still see those photos. The ends of his gorgeously graying hair are dyed red with his own blood, his eyes looking crazy. I used to be afraid he would choke on the blood in his sleep, that he would suffocate.

The second-hand smoke was suffocating too. His love was suffocating. His presence in my life still is. And then again and again – in my memory, which might not even be my own, I am saying to him ‘To be with you, to be forgiven by you for the things that I didn’t don’t do and those that I did but they weren’t wrong’. I am throwing the baton in the air and the splashes of paint leave traces on the canvas.

He once went on stage with a black eye. That night I covered up my bruises with a long-sleeved shirt or a black turtleneck that had become my armor. And then I helped him putting foundation on his face. His skin was much paler than mine so the foundation had to be almost white. We joked about how I am going to turn him into a mime and how our job, the way his hands fly above, the way all the eyes are on him the whole show, how his spine bent (he didn’t have to do it but that certainly was a look), is already a mimicry of a sort. He was a show himself. I am intimately touching his face with a sponge leaving white patches on his cheekbone.

‘Don’t you dare!’ I recall his yelling. ‘What if I fucking will?’ says my voice from inside the memory. And I am again reaching for the expensive instrument hanging on the wall. I am feeling his eyes, full of rage and disgust, on me but he does not move. I think now, he wanted to see me blight for himself.

I am yet again feeling his fingers in my hair. I clench his hair in my fist.

‘Hate me all you want but don’t go’ he said. I don’t think he actually believed I could hate him. Richard was desperate to be loved. He was admired already – by all the people coming to the concerts where neither Bach nor Wagner were the real stars, only he was. But love was different and he needed it to be visceral – not unattainable or sublime – real.

The familiar scent of him I could recognize anywhere. It was a mixture of tobacco, Armani perfume and the way his child room smelled. We went together to his childhood home once, when his father died and the family was selling the house. My excitement to see a part of him yet unknown to me quickly turned into disappointment as I saw the empty room with bare walls. It appeared all the furniture had already been removed, the wallpaper was stripped. It took us three and a half hours to get there and now he was standing in the middle of nothing, I bet, trying to visualize how it used to be. He never described what it was like. As the sunlight was falling on him from the window I was watching Richard from the doorway. He was beautiful that day, with his two-day greyish stubble, in a black turtleneck and a long coat. That is how I would like to remember him, I think, with the glint of sunlight in his eyes.

I am nothing but my memory.

My memory is scar tissue.

We loved each other – I hate him, I think. Love and hatred can coexist as they often do. I hated him for what he did to me but could neither despise him, nor be indifferent. Sometimes, when I do drink too much, I start hurting myself for real, by drinking even more, by flirting with dangerous-looking guys, by aggressively scraping paint residue from my skin. Then I think, maybe that self-affliction of mine is the reason for my hatred towards him. He is so deep in me that I cannot hate myself without hating him. I was him and he was me and who am I without you now?

But I want you more than I ever loved you. I think.

It’s a lie, that I only woke up in strangers’ beds. Of course I brought them home too. Out of spite, obviously, but there’s not only that. In the very beginning of our affair, you made sure I knew you didn’t want any strangers in the house. And at first, I followed the rule strictly. I never bought you, Richard, having no paramours during the tours. And I don’t blame you for whatever you had, whenever you did. It was great to have someone in our (was it ever out?) home though. Humbling because we could get caught, because I had to open up in this vulgar way, but exciting for the same reason. Shame and passion – weren’t it just you?

So many times I wanted to scream at you – and some many times I did. My voice was ranging in my own ears, the sound as loud as the drums being played next to one’s face. Once you broke my violin which I could not play well enough anyway. You grabbed it with both hands and threw it on the floor with all your might. Then you threw the bow in my direction, though I managed to dodge it. The wrecks scattered across the floor, remaining more of wood chips than smithereens. I gave you a slap, maybe with a fist. You yelled at me as I yelled at you. ‘Don’t!’, ‘What do you even know about what I feel?’, ‘Does it still hurt?’. Whose words were these? As we fought, we got rid of any intelligible words pretty quickly. Thankfully, insults didn’t do much harm. ‘Sluts’, ‘lapdogs’, ‘assholes’ were thrown in the air. When you yelled, you spat. My face was almost wet with you trying to articulate his exact feelings though it always ended up with ‘I fucking hate you’. That was your mic drop, mine was ‘I hope you die’. You laughed at that sometimes. I cried sometimes (and maybe he was the one who really did). And often you brought me tissues – dropped a pack on the floor and silently went away. I recall the sound of the door slamming. You always came back, except for once. ‘Hate me all you want but don’t go’ I cried out once when you were leaving me again, remember? There was no response, I think.

Why did your mom come to me on your funeral? Because I was weeping so loud everyone was looking at me and whispered? because I fell to my knees in front of your coffin? or because I was simply standing near it, hunched over, face down, for far too long for a man? I always assumed she just needed someone to talk to and here I was, flesh and bone. You were flesh and bone too but I’d prefer for you not to be there. I cannot wipe the image out of my head. Every haunting idea I always drew but I could not manage drawing your body. You looked dead in the most nauseating way possible. Sometimes at other people’s funerals I had a feeling that the body would suddenly wake up and laugh at everyone around buying into the silly joke they set up. That day I could not imagine you alive. Maybe our whatever-that-was was never visceral enough for you, sure, but that image of your flattened, masked face and frozen chest, ups and downs of which I used to count when my insomnia had been overwhelming me, was. Your eyes were closed, lips pursed, even though you always slept with your mouth a little opened, your skin even paler than usual, and you had been already called a half-dead and a-real-aristocrat before. The lower half of your body was covered because of how mangled it was after the crash, but most visitors, I am sure, did not even notice. I never sketched you, Richard, you know that. How could I never draw your body but your corpse?

Why did you come to me the day we met? You certainly weren’t looking for a new prey or a one-night stand, that was never your thing, or was it? I certainly should have asked you back then. But when ‘then’? When was the right time to ask? Was there the right time to ask? Did we have time at all? Did I have the right words to say the things we both needed to hear or was there never that kind of strength in me? I should have, of that I know, asked so many questions that I only start to verbalize now, sitting in my studio surrounded by the demolished canvas. This room turned into my personal shrine to you, Richard, to the person I hate the most and crave no less. It’s a corner of my old house, the room I rent from its new owner. He finds it prestigious that a painter works by his side even if he hasn’t produced anything since his boyfriend’s so-called accident. I never let you get in this small room that smells acrylic paints and stuffiness and how I wish I did. I crashed all these paintings of mine because I had an impulse. Because I hated every stroke of you on the canvas, and were there many. Because they showed that flimsy self of mine in full glory. Because of this and that and because of the third-fourth-fifth thing. There’s this ugly thought – it was the end. I didn’t know thou at all.

Vera Podell is a Russian-born writer and photo artist. She writes in three languages which are English, Russian and German. Vera's writing is primarily focused on the topics of memory and how it impacts our identity.